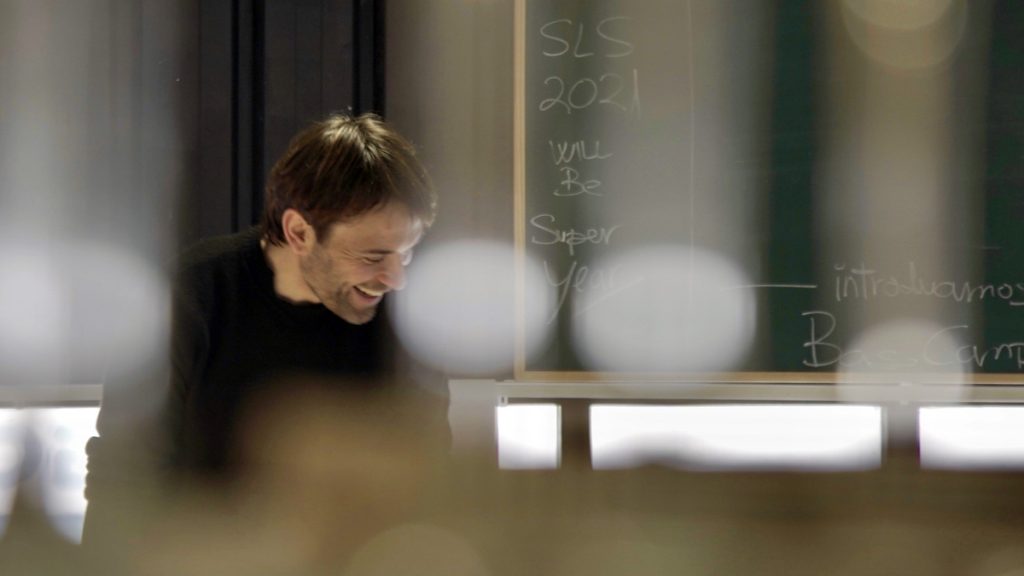

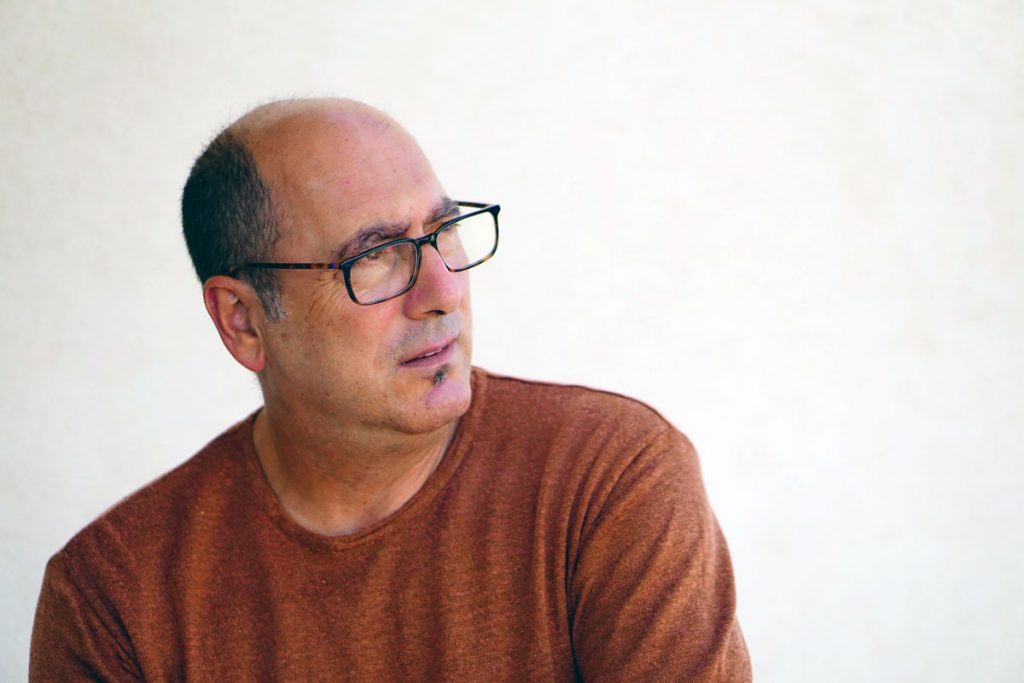

Jordi Moya understands lighting as a key constructive material in the creation of ambiences and atmospheric interiors. With a long and varied career, extensive technical knowledge and an inexhaustible enthusiasm for discovering new visual languages, Moya is a remarkable figure who has developed countless architectural projects and who specialises in the lighting of works of art, exhibitions and museum spaces.

Despite having a degree in industrial technical engineering, you have focussed your professional career on lighting design. Is the development of lighting projects more science than art or more art than science for you?

For me, it’s a balanced coexistence between two worlds. Depending on the project, the lighting is more inclined towards one or the other, but both are always present in some form. I frequently defend the need for specific studies for lighting design that include technical training, to learn about the tools we work with, and artistic training, to design the effects used to create different atmospheres. Lighting designers work with architects and interior designers and it’s important we understand their language, their vision, their intentions, etc. Because of this, we need specialised training in colours, properties of light, chromatic dispersion, the golden ratio, spatial distribution, visual perception and so many other aspects. To answer your question more directly, I think it’s important to know both worlds in order to develop a lighting project from the design and execution stages to the final touches.

You have also studied set design, theatrical machinery and set space and have completed higher studies in photography. Are these disciplines important for developing creative lighting?

Culture is made up of different pieces of knowledge from very different fields and all of these help us to get to know the world and develop a greater sensitivity towards certain aspects. Speaking of the subject, the phrase ‘shadow cannot be a surprise’ comes to mind. I studied photography initially and worked for a few years as a photographer in the analogue era, before entering the world of lighting, which I entered by doing music concerts. Photography helped me figure out how to focus my attention on special lighting moments, to hone in on the most attractive visual elements of the 360 degree reality we live in. Set studies taught me about an expressive language in which light shapes and defines the space. It helped me incorporate the spectator’s point of view into my designs. All of this knowledge allows one to understand light effects and personally I would say these disciplines helped ‘train my eye’.

You design lighting projects of all kinds, but since 2000 you have worked as an illuminator for temporary exhibitions for various centres and museums. How did this specialisation come about?

My specialisation started a bit by chance. My godmother, Laura Baringo, designed temporary exhibitions in Barcelona and she had problems with lighting them, so she asked me if I could give her a hand. At that time I was doing stage lighting for concerts, where my work was really ephemeral; after long hours of concept development, assembly and programming, everything ended after one hour of show. So what really attracted me was the time dimension shift — that the lighting creations had a somewhat longer existence. Laura’s highly demanding nature and my passion for discovering the visual possibilities of museum luminaires pushed us to complete very interesting projects that were admired wherever we went. Until then, exhibition lighting was in inexperienced hands; electricians and assemblers would just put a spotlight up wherever they were told to. No one contributed any technical input or lighting experience. After lighting a number of exhibitions, cultural centres began to appreciate the difference in quality and asked us to collaborate on their projects. This new situation, together with my desire to have my own project, led me to specialise in museum lighting.

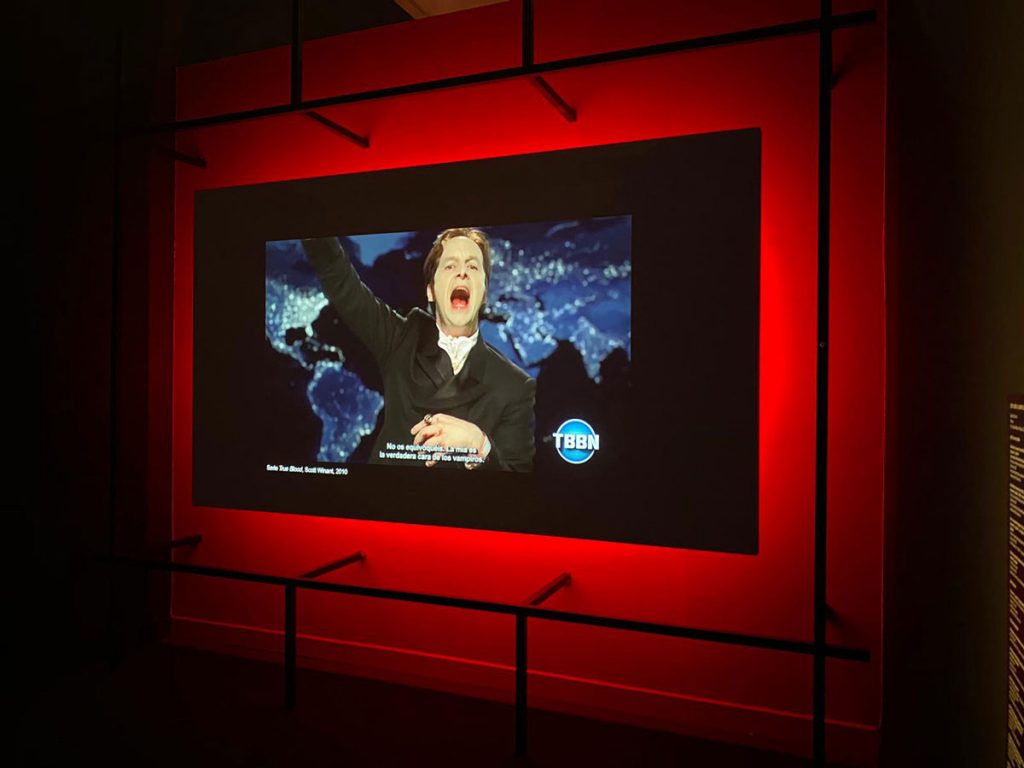

What are the basic aspects involved in lighting temporary exhibitions?

In short, the basic aspects would be creating the environment desired by the designer and that the exhibited works look good. These two objectives must be achieved in a pleasing manner; without glare and without sudden changes in the environment. In heritage exhibitions, the requirements of the curators vary depending on the material used in the work and their criteria. To give you an example, I illuminated an exhibition of drawings in which the owner wanted to do it with 200 lux, when the paper should not be exposed to more than 50 lux. Another time, I was working on an Alphonse Mucha Museum exhibition at the Casa Lis in Salamanca; the curators demanded 35 lux in the exhibition lighting and also controlled the night light and the surveillance light below that level.

Have the technical requirements and visitors’ preferences in terms of lighting changed a lot since 2000?

The technical aspects have changed radically since LED technology was invented. In 2000 museum lighting basically just used tungsten light sources; various halogen bulbs. These had a lot of drawbacks: the colour temperature would often change, they emitted UV and IR radiation that we had to filter out, they didn’t last long and they weren’t very efficient. Nowadays, thanks to LED technology, lighting is much more efficient; it doesn’t emit UV or IR radiation, the colour temperature doesn’t change when you adjust it and it’s very long-lasting. However, I don’t think visitors’ preferences have changed at all. LED lighting has given us much more precise tools that allow us to control the ambience better, creating more comfortable spaces. Visitors just want to be able to see the exhibits properly, read the information that goes with it and have a pleasant experience. I think this will always be the case.

As an illuminator, do you think LED strips are a good resource to be creative in the projects you carry out?

It is an indisputably useful tool. Since the creation of LED strips, there has been a greater integration of lighting in architecture. Being able to trace the lines or architectural elements such as a staircase, a roof or a fence, takes the project to another dimension. Highlighting the architecture without using poles and projectors allows you to enjoy it during the day in all its splendour, with its visual games of lines and volumes, and simply turn it on at night, showcasing its scenographic power.

What are your favourite applications?

Countless! There really are many, but one of the ones I like the most is not having the light source concentrated in one point, especially for lighting display cabinets or very large exhibition spaces that have built-in linear lighting. By having the light in a line, I am often able to get rid of shadows. This is a great advantage since it eliminates the harsh shadows that a spot projector generates. In addition, the fact that the strips are beginning to include a large number of accessories such as diffusors, magnifiers, wireless controls and flexible versions offers us a wide range of tools to adapt to new challenges. Digital LED is another excellent application that has given us a whole new aesthetic, a new visual language: dynamic light. With digital LED you can give ‘life’ to interiors and even transform them into LED screens – new worlds that only LED strips can provide us.